Definition Of Interpretation In Literature

Chapter Five: Reading and Interpreting Literary Works

Interpreting Literary Works

We discuss the following subjects on this page:

- Interpretation Introduction

- How to Interpret Literary Texts Using Schemata

- Symptomatic and Explicatory Interpretations

Interpretation Introduction

Interpretation is the process ofmaking pregnant from a text. Literary theorists accept different understandings of what interpretation is, what constitutes a "proficient" estimation, and whether we should even be interpreting literary texts at all. Frank Kermode, for example, claimed that only insiders are able to interpret stories properly just even they are decumbent to errors. Susan Sontag argued that we should refrain from interpretation and confront the literary and creative work "equally is" so we tin can experience it on its own terms. Umberto Eco stated that literature allows for a range of interpretations simply some are better than others. Their disagreements center on the freedom of the reader. Should the reader be able to make any pregnant whatever from a text? Does the text resist estimation and insist on being read on its own terms? What constrains the reader's freedom to interpret? Do constraints arise from the author, from within the text itself, from within the reader, or from inside the culture? (And whose culture, we might ask, should make up one's mind the proper interpretation: the reader'south or the writer's?)

How to Interpret Literary Texts Using Schemata

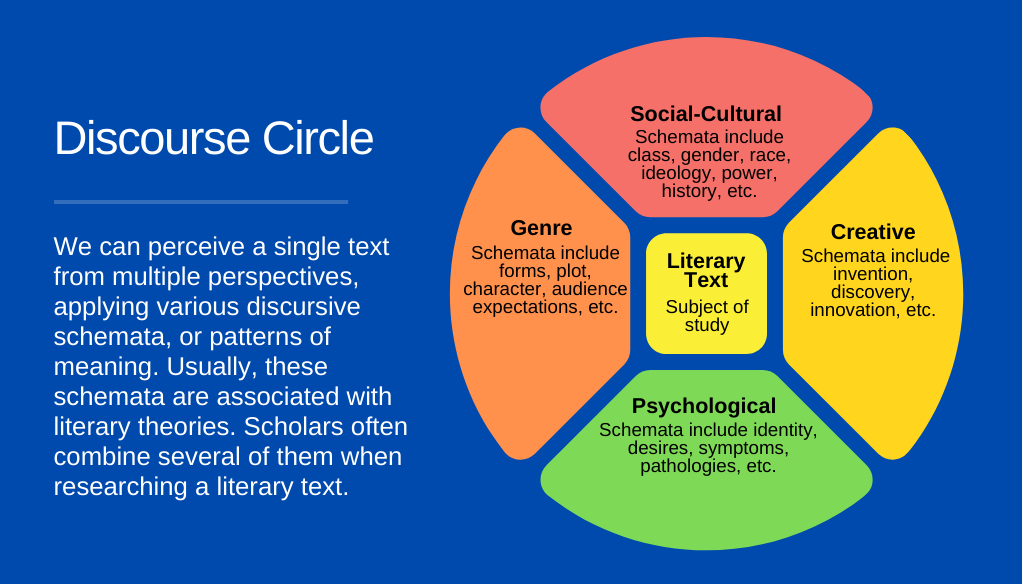

At that place are numerous schools of interpretation, each with their own interpretive schema. A schema is a broad theoretical framework for agreement the world. Nosotros discussed a variety of these theoretical frameworks in the previous unit. To oversimplify: psychoanalysis uses the schema of personal development; Marxism uses the schema of class struggle; feminism uses the schema of gender inequality; Christianity uses the schema of sin and redemption; etc.

Producing an Interpretation

- Notice pregnant details in the literary text

- Detect a blueprint in those details

- Map the design found in the literary text to an interpretive schema

- Merits that X in the literary text is actually Y from the schema

Notice that estimation moves from the specific to the full general, from the details of the literary piece of work into more conceptual terms. About critics only utilise some, not all, of the details from a literary work in the estimation. If you lot disagree with a critic, you can pose a contrary interpretation by claiming that the critic overlooked significant details from the literary work, formed a misleading blueprint, and mapped those details to the wrong schema. Finally, yous offer your ain interpretation, following the steps outlined to a higher place. Many critics combine interpretive schemas. Also, it is acceptable to be suspicious of schema and of overarching narratives, especially ones that supposedly "explain everything." Nosotros can use schema and include a caveat that while they are useful nosotros demand not grant them gospel truth.

Symptomatic and Explicatory Interpretations

David Bordwell, in his bookMaking Meaning(which is primarily about moving-picture show estimation simply works quite well for understanding literary interpretation),discusses ii major interpretive traditions:explicatory andsymptomatic. Asymptomatic reading is i in which the critic treats the text with suspicion, as though it disguises its true intentions. Your goal, using this method, is to become the text to "confess" its significant past pointing to "symptoms" in the text. Freud stated, "A symptom is a sign of, and a substitute for, an instinctual satisfaction which has remained in abeyance; it is a consequence of the procedure of repression" ("Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety" xx.91). The symptomatic critic is looking for signs that betray the existent intention of the text or the author, just equally Freud seized on forgotten names or slips of the tongue equally symptoms that more accurately revealed the patient's state of listen than did their explicit statements. In a symptomatic reading, a reader might argue that a text that seems anti-racist hides a racist intent or effect.

Anexplicatory reading is one in which the critic turns implied significant into explicit significant. An explicatory reading does not treat the literary text with suspicion. For instance, you might discover a text that seems anti-racist, and your interpretation explains how it is, in fact, anti-racist.

Bordwell argues that critics often switch the way they read depending on the literary work. Some literary works – ones that critics believe are ideologically abusive – are read symptomatically, while other works – those critics believe are ideologically healthy – are read using explicatory methods.

Bordwell presents the following passage aboutexplicatory criticism:

On a summertime day, a suburban begetter looks out at the family lawn and says to his teen-aged son: "The grass is so tall I tin inappreciably come across the cat walking through it." The son construes this to mean: "Mow the lawn." This is animplicitmeaning. In a similar way, the interpreter of a film may accept referential or explicit significant as only the point of departure for inferences about implicit meanings. That is, she or heexplicatesthe motion-picture show, just as the son might turn to his pal and explain, "That means Dad wants me to mow the lawn." Explicatory criticism rests upon the belief that the principal goal of critical action is to ascribe implicit meanings to films. (Making 43)

The flip side of this prototype is that critics tend to perform symptomatic criticisms on texts they consider ideologically suspect. Bordwell explainssymptomatic criticism in this passage:

On a summertime twenty-four hours, a father looks out at the family lawn and says to his teen-aged son: "The grass is and then alpine I can hardly run across the cat walking through information technology." The son slopes off to mow the backyard, but the interchange has been witnessed by a team of alive-in social scientists, and they interpret the male parent's remarks in various ways. One sees information technology as typical of an American household's rituals of ability and negotiation. Another observer construes the remark equally revealing a characteristic bourgeois concern for appearances and a pride in private property. Yet some other, perhaps having had some training in the humanities, insists that the father envies the son's sexual proficiency and that the feline image constitutes a fantasy that unwittingly symbolizes (a) the male parent'due south identification with a predator; (b) his desire for liberation from his stifling life; his fears of castration (the cat in question has been neutered): or (d) all of the to a higher place. […] Now if these observers were to propose their interpretations to the male parent, he might deny them with great vehemence, but this would not persuade the social scientists to repudiate their conclusions. They would reply that the meanings they ascribed to the remark were involuntary, concealed by a referential meaning (a report on the height of the grass) and an implicit meaning (the order to mow the lawn). The social scientists have constructed a prepare ofsymptomaticmeanings, and these cannot be demolished by the father's protest. Whether the sources of meaning are intrapsychic or broadly cultural, they lie outside the conscious command of the individual who produces the utterance. We are now practicing a "hermeneutics of suspicion," a scholarly debunking, a strategy that sees apparently innocent interactions every bit masking unflattering impulses. (Making 71–72)

Critics employing the symptomatic approach look for "incompatibility between the moving picture's explicit moral and what emerges as a cultural symptom" (75). In other words, the symptomatic approach looks for instances that point a text's explicit message hides a less flattering message. Such symptomatic readings warn people non to be fooled by appearances; the true, nonetheless disguised, intentions of a text ― its "repressed meanings" ― are apparent if you lot know how to look for them. Explicatory criticism, by contrast, urges the audition non to miss the text'southward implied letters.

- Practice your reading skills on one or both of the poems below using explication, analysis, or comparison/contrast:

Give-and-take

The word bites like a fish.

Shall I throw it back free

Arrowing to that sea

Where thoughts lash tail and fin?

Or shall I pull it in

To rhyme upon a dish?

–Stephen Spender

Pitcher

His art is eccentricity, his aim

How non to striking the mark he seems to aim at,

His passion how to avoid the obvious,

His technique how to vary the avoidance.

The others throw to be comprehended. He

Throws to be a moment misunderstood.

Nonetheless not besides much. Not errant, bare-faced, wild,

Just every seeming aberration willed.

Non to, yet even so, even so to communicate

Making the batter empathise also late.

–Robert Francis

- Do an interpretation of one or both of the poems higher up, using either an explicatory or symptomatic approach.

Write your answers in a webcourse discussion page.

Get to the Discussions area and find the Interpreting Literary Works Word. Participate in the discussion.

Get to the Discussions area and find the Interpreting Literary Works Word. Participate in the discussion.

Definition Of Interpretation In Literature,

Source: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/strategies/chapter/interpreting-literary-works/#:~:text=Interpretation%20is%20the%20process%20of,interpreting%20literary%20texts%20at%20all.

Posted by: samonsatrom1955.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Definition Of Interpretation In Literature"

Post a Comment